I have previously uploaded two stories of my father’s time as a POW (links below).

To mark 75 years since liberation this account fills in the gaps. It is a mix of sections from his writing – life story, emails to the Goldcoaster network and my additions; the latter two are in italics. As I have said elsewhere, I have not edited my father’s vocabulary or spelling to make it more ‘politically correct’. I have added sub-headings.

I don’t think he held any grudges about that time. Growing up in Indonesia he had developed a more Eastern view of the circularity and ups and downs of life. In my view it is always an horrendous time for all involved in war and conquest and I hope we are not forced to go that way again.

This is Peck’s story:

Beginnings in Holland

In 1917 my parents got married and in September 1918 on the 24th I was born. My father (Marius) was employed by a chemical manufacturing company in Naarden (mother, Antoinette, ‘Etty’) was a nurse. This town is to the east of Amsterdam.

The first war (WWI) had ended and there was great demand for many products. A number of large corporations had sugar producing estates in Indonesia on the island of Java. There was a great demand for employees and the wages were very good and on top of that the staff received large bonuses at the end of the years. Due to the war there was a large demand for many goods one of them was sugar.

The move to Java

My Father applied for a job as chemist and was taken on by one of these corporations, he had to sign a contract for six years and at the end of that period he was given a 6 months holiday, the company paid all travel expenses. These sugar estates were always in the country and usually 40 or more KM from any town. Once a month we use to go to town to purchase supplies for a month. It was always a great occasion and we children use to get a special treat of lemonade and Ice cream.

(They arrive in Java in 1920. Frank is 1½ years old. While Marius works for the Dutch Indes sugar industry Etty uses her nursing and midwifery training to run a polyclinic on the Estate for the local Indonesians, which is always busy. The Rups children hang around and watch, so learning about the treatments. The children are schooled in Indonesia.)

Conscription into the army

In 1933 I passed the intermediate and it was decided that that was enough. Every boy of 18 had to serve in the army (Royal Indonesian-Netherland army) for a period of six or twelve months, depending on which branch they were put in.

I asked for the transport section and after a few months I asked to be transferred to the mechanic section. That was granted and that was a much better job. We had no parade and were not disturbed in our work. The regulars showed us how thing were done and it was very useful when I came to Australia. I was able to do most repairs myself.

I worked with Kolf & Co, Library and Stationers (for whom Frank is branch manager at Solo and Djocja) until the war started in 1942. I was called up and detailed to a gun unit to do the maintenance of all the vehicles. One day we were told to move and face the enemy, we drove all night and finished up in a queue on the way to an airport. But the Japanese had occupied the airport and used it to send bombers to bomb us. All day long they came over and dropped the bombs and I did nothing else but run from one ditch to another and I got out of it ‘Scott free’. We were ordered to retreat to our base in a small town near Bandung.

Capture by the Japanese

The next day the end of this war was announced and the following day Japanese troops entered our barracks and took all the weapons away. We were now prisoners of war. One day we were all called on parade and the Japanese brought two of our men into the camp. They had been beaten and now in front of us they were shot, all because they had gone home to their wives that night. After a few months a call was made for four drivers. I came forward and was selected. The Japanese gave us each a truck and we had to drive to the West Coast of Java. The next day we had to drive to the beach and there was a large supply of all sorts of things the Japanese had unloaded from their supply ships that came with their landing force.

Frank’s father (Marius) and brother (Hans) before the occupation, in front of the house his mother (Etty) was taken from by the Japanese. All members of the family were interred.

The Japanese loaded the trucks and we had to drive to a township where everything was stored. We lived with the Japanese soldiers and ate from their kitchen. We were treated as equals. It was here that the survivors of the Perth and Houston were kept in a camp. We were not allowed to talk to them. They looked a sorry lot. After the job of moving all this supply we drove back to the camp we had come from. We were used to do all sorts of different jobs, such as cleaning buildings and parks etc.

Work as an orderly in the camp hospital

Then one day the Japanese asked for a number of people to work in the hospital. I volunteered and in the afternoon we marched out of our camp. When we entered the hospital there stood a group of English soldiers on parade. As we marched in they marched out under command of Dr. Dunlop (Weary Dunlop). The Dutch doctor in charge of the hospital told us that all the hospital was divided in a Dutch section with the Dutch personnel and an English section with English personnel. The English medical staff was taken to the prison camp and we had to replace them. (‘The Japanese decided that the hospital should be one unit, they asked how many English staff there was and told our camp commander that they wanted so many people to go to the hospital to work’. Goldcoasters email 28/12/1999). Well there were a few orderlies and doctors among us but the rest had no knowledge of medicine (and also did not know much English, you can imagine that first night).

We had presumed that we were wanted for maintenance duties. Anyway we were all detailed to various wards. That night there had to be staff on the wards. No one wanted to take the contagious disease ward. A regular army orderly (from the medical corps) said to me, ‘come on we take that ward, I shall teach you the ropes’. So I started my career as an orderly, this followed me right through to the end of the prison period of three and a half years.

Because of the haste we did not know where we were to stay. That first night I spend sleeping on a blanket next to a patient who was in a terrible state. He had been wounded and had lost so much weight that he was skin and bone. He had the worst bedsores I ever saw. He needed a lot of attention because he was crying all the time and had dysentery as well (…he needed constant cleaning…but he survived that part, we got him better). I had some idea of nursing because I had picked the knowledge up when my mother was looking after the sick people on the estates.

The next morning the doctors came to their appointed wards and started to straighten things out. We were given lectures in physiology, pathology and how to nurse but in my case I had learned all I needed to know from my mother.

This all took place in Cimahi a town near Bandung. The hospital is still there and used.

For eight months I worked in that hospital. The Japanese never came near us because of the T.B, dysentery and diphtheria we were nursing. In those early days it was still easy to buy various foods such as meat, vegetables, etc and I use to cook up something nice for Xmas. [1]

(‘The best chance of survival was to have a friendship bond of two or three people, who help one another under all circumstances. I was lucky to be in that situation. I visited my friend in England a number of times over the years. He rose to a high position in one of the Banks. The last time we met, we knew that that was the last time, when we said good bye he cried. This was after we had made our separate journeys for some forty years. Time does not mean anything in these matters’)

On the move

After the hospital we were sent back to the prison camp. Here they made us in three groups to be sent somewhere. After a month we were told to pack up and come on parade for our departure. All the possessions we had accumulated were too much to carry and we had to make a selection that could fit in a kitbag and a shoulderbag. We were put on a train with all the windows covered. We arrived in Jakarta and were marched to a prison camp.

We arrived at Jakarta (Batavia) and were billeted in the Bicycle camp, which was a notorious camp, because the Camp Commander had strange ideas, such as calling on parade at 2 o’clock in the morning and if you were not fast enough you got a belting. He did many mean things. Luckily we were there for only a short time. (Goldcoasters email 3rd January 2000)

After a month we were rounded up and taken to the port (Tanjong Priok). When we were all counted and divided it was 1 o’clock midday and the sun was shining all day. There we had to get on board of a ship by climbing up a ladder. Arriving on the deck we were made to go down on a ladder into the hold of the ship. (At the bottom of the ladder were a number of Japanese soldiers with bamboo sticks beating everyone, making them crawl under.

What the Japs had done was divided the space from the floor to the deck in three sections. We had to occupy a three storied area…plus all the hundreds and hundreds of cockroaches)…and we had to crawl into the darkness underneath the platform. The later arrivals had to get on the platform. To make us hurry up we were beaten with sticks. It was nearly unbearable as the sun heated the steel of the ship and it was like being in an oven. I stripped to my underpants and the sweat was running of my body. Some men fainted. At last the ship started to move and we left the harbour. I crawled in some distance and took up a position against a post.

After an hour or so we were told that if we wanted a drink, there was a large tub with hot tea in a corner (on deck) and we were allowed to come up and have a drink. There was a long tea queue. I went back inside got my pannikin (dish) and eating utensils and went back. Once I was on deck I found myself a comfortable place where I intended to stay and sleep. If we were torpedoed I could at least swim and perhaps save myself. Many of the poor fellows were so disheartened that they just remained downstairs, got seasick.

Arrival in Singapore

It took four days to arrive in Singapore in the driving rain. I climbed back into the hold to get my pack and went back on deck. As soon as we had docked we were taken off the ship and loaded onto lorries. They took us to Changie. We were taken to do various jobs in the garden they had started. The produce was for the Japanese troops not for us.

Dysentery and a return to nursing

After a few months in Changie camp we were taken back to the docks and put on a ship. There must have been a hitch because we did not move. Dysentery started to break out and one day all the people that had dysentery were taken off the ship. I was amongst them and we were returned to Changie camp. I was sent to the dysentery ward of the hospital. After a few days I recovered, but now there were no Dutch units left and I didn’t belong anywhere.

Because I had assisted with nursing, I was kept in the ward as an assistant. This was a bad time. The bacillary dysentery we could mostly cure but there were no medicines for the amoebic dysentery sufferers. As this disease is a slow and chronic complaint we had to give the patients enemas every day of Acraflavin, which is a disinfectant, in the hope that we could delay the progress of the disease.

Then one day troops started to return from the Burma railway. They were a sorry lot and many died. We had to work day and night to try to get them better.

Changi and Kranji

Then the big move came. The Japanese had used a lot of the prisoners to clear an area of land that was to become an airstrip and needed the buildings of our camps for their own troops. We were moved to Changie Jail. The civilians had been interned there, but we were a much larger group and many huts were built outside the jail.

Part of the hospital was moved to Kranji a camp not far from the naval base in the North of the island. I was not a patient and had to come to the jail. After a few months I was sick again and I was sent to Kranji. Here I met up again with the orderlies from the hospital.

Finding ‘mates’ and food

With two of them we formed a group and that became important because now the worst time started. Very little food and people started to get berry berry and other diseases due to lack of vitamins. Prior to this time I had made friends with an Australian soldier at the time we were in the jail. Arthur Gibbs, or Gibby….The group we formed consisted out of Jim an orderly, Harry a chemist and myself. I was employed in the garden.

There was a canteen with very meagre supply, cigars, palm oil, blachan (a shrimp paste). Our rations consisted out of rice, a thin bitter soup and one or two dovers (rissoles) rice mixed with dried fish and fried in the oil. Breakfast was porridge of rice mixed with crushed corn. It was cooked the night before and in the morning it was heated mixed with a bit more water. We would get a scoop of it plus one spoonful of sugar.

Because I worked outside I was able to steal some food. A sweet potato, some spinach leaves etc. I knew many weeds that were edible. And other things like the pips of the Jack Fruit. The Jap guard often had a piece of jack fruit and threw the seeds away, roasted they are good eating. The problem was to get wood for a fire. The camp was under Gum trees and there were some branches but the bulk of wood came from the cemetery.

Cemetery duty

There were so many people dying there was always a call for volunteers to go with the stretcher to the cemetery. This was up a hill and there were many Rubber trees. As that area was out of bounds there was always plenty of dead wood to be gathered. So I regularly volunteered to attend a funeral. James and Harry had their own sources to get something extra and we divided this.

Food savvy

In the period of the dry fish supply I discovered that the English cooks filleted the fish and threw away the bones. So I asked if I could have the bones and I minced them to a paste which was something extra to eat with the rice. The other item that helped was the Blachang, the smelly paste. I fried it in oil also as an extra taste and it must have had some nutrition in it.

At last we heard that the Japanese had given in and the war was over. It did not take long and our troops started to arrive. Amongst them were welfare people who did their best to bring us comfort. They had vans and handed out tea and biscuits.[2]

The Aftermath

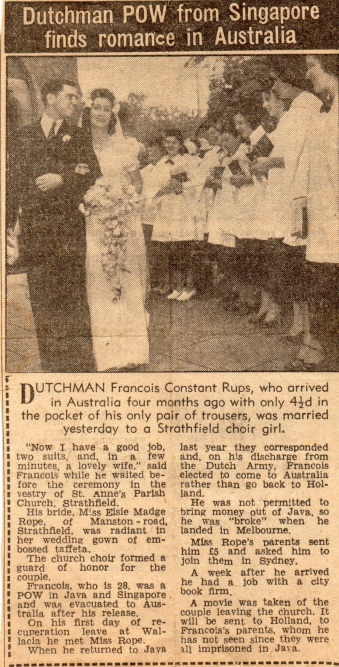

The authorities did not want me to leave Singapore for my recuperation after the three and a half-year in the prison camp because I was a medical nurse and there was a shortage of nursing staff. I had my heart set to be sent to Australia and not Holland. Then at some time beginning March 1946 an announcement was made that after the end of March no more Dutch troops were to go to Australia. I moved heaven and earth to be sure that I would not miss out.

The Event appeared in two newspaper articles. The article above has been saved in the family archives with no reference. The other can be found at,

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/98375220?searchTerm=rups&searchLimits=dateFrom=1947-04-13|||dateTo=1947-04-13 (Sunday Mail, Brisbane)

age 82 years, the time of writing.

Frank died in 2008, at the age of 90 years. In his self-written obituary he wrote,

‘I have always been thankful to Australia and the people have always treated me well.’

c. A. Maie 2020

[1] Rusty Rups’ Xmas in the camps.

[2] Rusty Rups’ liberation from Kranji

We left Elizabeth and Anthony at the end of

We left Elizabeth and Anthony at the end of

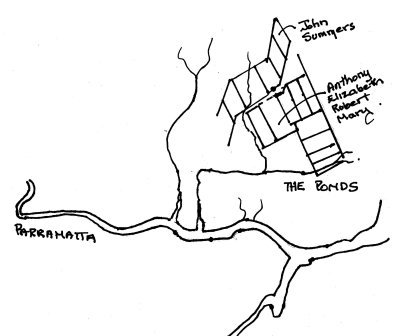

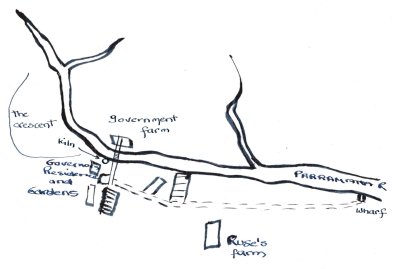

Rose Hill c. 1789

Rose Hill c. 1789